I have no internet at home at the moment, hence the pause in posts. I haven’t forgotten about Chronica Minora. I just don’t find the WordPress phone app comfortable enough to use.

Bafflingly bad history

The world would be boring if we all agreed on everything all the time. People disagree with each other in every field of endeavour, and history and archaeology are no different. However, sometimes you come across a story and it’s obvious that something just isn’t right. It can be that somebody has twisted the facts, that they’ve made a leap not supported by the evidence, or that somebody is seeing what they want to see as opposed to what’s really there.

The last two definitely apply to this story, to which I came across a link to an article on Facebook earlier: King David’s palace found, Israeli team says.

Now, that’s not to say that they haven’t found a significant historical site. In this case it’s Khirbet Qeiyafa, a fortified area near Jerusalem that has been under excavation and study for years. According to Wikipedia (I know, I know, not quite authoritative) it is known by local Bedouin’s as Khirbet Daoud, or David’s ruin. However, that doesn’t necessarily mean it’s actually David’s. Any number of sites across the world have become associated with historical and even mythical figures; there’s one in a forest near where I grew up called the Giant’s Grave, but that doesn’t mean there’s an actual giant buried in it.

The authority of the finders isn’t in question; they are professionals from a university and a state culture agency. However, they seem to have seriously jumped the gun on this one.

[Yossi Garfinkel, a Hebrew University archaeologist] said his team found cultic objects typically used by Judeans, the subjects of King David, and saw no trace of pig remains. Pork is forbidden under Jewish dietary laws. Clues like these, he said, were “unequivocal evidence” that David and his descendants had ruled at the site.

Er, no. I’m not an archaeologist and I know that. It is very dangerous to make a sweeping conclusion based on a lack of evidence, as opposed to a supposition based on some evidence. For me, the lack of pig remains simply means that there’s no evidence that pigs were slaughtered on the 3,000-year-old site. One would be entitled to suggest that, taken with typical religious artifacts, this means a Jewish community ruled it or lived there – it does not mean that it was a palace owned by one of the most important figures in Jewish history.

As the article by Max Rosenthal notes, other researchers think the site could have been built by the various other ethnic groups that lived and fought over the area at about that time. Granted, I haven’t been involved in the dig and haven’t seen the artifacts or filed reports, but this seems to be a case of over-interpreting data.

History is already fraught with enough dangers and missing links – we shouldn’t be out to add a few new ones to it.

Columba – the other patron saint

The rebuilt abbey of Iona

This year marks the 1,450th anniversary of St Columba’s arrival on the island of Iona, off the coast of Scotland. If you’ve read your Bede well (as I know you have) then you’ll remember him as one of the paramount evangelists to northern Britain.

Pictish kingdoms; the Irish Dál Riata is the large area to the southwest

Columba (d. AD597) is of vital importance for early medieval insular studies, because the monastery he founded at Iona became one of the most influential in Ireland or Britain. Its monks went on to evangelise not only the Picts but the English, founding the likes of Lindisfarne, which in turn became one of the most important religious sites in Northumbria. Bede praises the Irish for having brought Christianity to the English when the Britons, the Christian descendants of the Romano-Celtic population, had refused and remained apart.

Columba was one of the many Irish who ended up in “exile for Christ” (peregrinatio), though in his case the story is that he had to leave Ireland after many people died in a battle over a manuscript of hymns (they took their hymn books seriously in those days). He fled Donegal for Iona, which then was part of the Irish kingdom of Dál Riata, which incorporated the northeast of Ireland and southwest of modern Scotland.

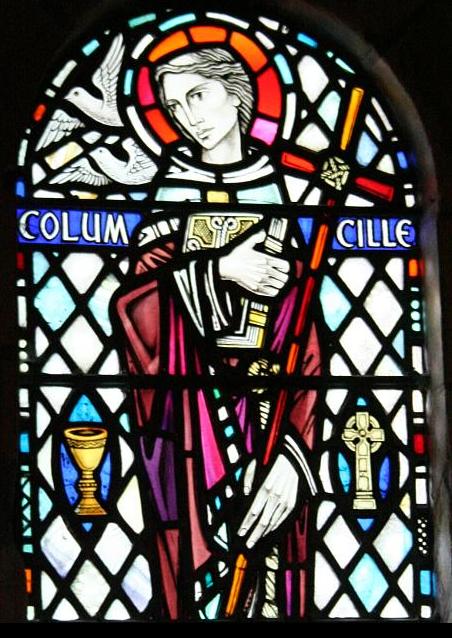

Columba commemorated in stained glass at the abbey

What tends to be overlooked is that he is one of the three patron saints of Ireland. Everybody knows Patrick, and everybody has heard of Brigid, but Columba (or Colmcille as he was known in Irish) is less well known across most of our island. His missionary endeavours and monastic founding spree make him a saint par excellence, particularly because Christianity was still bedding in somewhat amongst the Irish and Picts at his time and hadn’t taken off at all among the English. His groundwork, then, contributed to the shaping of the islands’ history.

Fun fact: The first recording of a monstrous creature near Loch Ness is in Adomnán’s Life of Columba. The creature had killed a Pict and was about to eat one of Columba’s monks, but he banished it to the waters with the power of prayer.

I quite like the Life of Columba as a text. It has a lot of the standard imagery of medieval hagiography, a genre which is rich in miracle stories and other events without intending to be strictly historical. They contain basic biographical details, but are designed to commemorate the memory of a saint and to spread his or her cult, as well as holding the saint up as an example of how to live a good Christian life.

The Life of Columba is particularly important because it was written at a very early stage of Christianity in Ireland, and yet it is completely engaged with the genre, showing that the author, Adomnán, abbot of Iona (d. AD704), had read widely and knew exactly how to shape the tale of his predecessor in order to promote his memory. He shows that Columba was saint on a par with any saint from the Holy Land or continental Europe.

For example, he is granted prophetic visions as well as the power to work miracles; indeed, one of the final miraculous events in the Life is Columba foreseeing his own death. And following his death, Adomnán writes:

After his soul had left the tabernacle of the body, his face still continued ruddy, and brightened in a wonderful way by his vision of the angels, and that to such a degree that he had the appearance, not so much of one dead, as of one alive and sleeping

It is a political as well as religious text, because Iona was under particular pressure at that stage because it was out of step with Rome and Britain on the calculation of Easter. This might not seem like a big thing to us, but it was profound then, because it meant that the church at Iona was effectively outside Christian orthodoxy. Part of Adomnán’s motivation was to show that the founder of Iona was favoured by God, which in turn would have strengthened Iona’s case for holding to the old Easter calculation.

Quite what Columba, a man who had converted kings and been a prolific writer, would have thought is unknown. Still, his legacy is uncontestable, and President Michael D Higgins has urged contemporary Irish emigrants to consider his example:

Modern migrants do not generally make decisions in such dramatic circumstances as Colmcille’s but, whether they see themselves as exiles or not, at some point many will ask themselves what they have to share and to teach to their new neighbours; how they may influence the society in which they make their new home; and what they may absorb there, changing themselves in the process.

It’s sound advice. I think Columba would have agreed.

It’s all Greek to me

On the heritage trail

At Wells House in Co Wexford launching Irelands largest heritage trail are Colm Morris, Bridget Murphy, Minister of State for Tourism & Sport Michael Ring, Louise Cullen as Lady Frances Ray Murphy and Paul Reck. Picture: Patrick Browne

As I keep harping on about, history and heritage is everywhere, which is why the fact that Co Wexford now has the longest heritage trail in the country caught my eye.

The trail, officially launched this week, is a driving route that takes in 32 sites covering everything from landscape gems to cultural attractions.

A press release issued by the organisers detailed the sites:

Ferns Castle, Colclough Walled Garden, Tintern Abbey, Ballyhack Castle and Selskar Abbey; National Parks & Wildlife Service managed Wexford Wildfowl Reserve; Wexford County Council initiatives of Enniscorthy Castle, National 1798 Rebellion Centre, Vinegar Hill Battlefield, Irish National Heritage Park, Duncannon Fort, Browne Clayton Monument and Hook Lighthouse (in association with Commissioners of Irish Lights); Enniscorthy town, Fr. Murphy Centre, Gorey Town, Johnstown Castle (Teagasc) and the Irish Agricultural Museum, Wexford town, Our Ladies Island, Loftus Hall, Ros Tappestry, Dunbrody Famine Ship, New Ross Town, Dunbrody Abbey, Oulart Hill, Kilmore Quay and Saltee Islands, Ballymore Historical Features, Wells House, Tacumshane Windmill, Craanford Mill and The Kennedy Homestead.

It actually seems to have something for everyone, which makes me wonder why I haven’t been to the county yet.

Wexford is an important county from a historical point of view. Just a few weeks ago the visit of Caroline Kennedy, daughter of JFK, to the family’s ancestral home in the county brought it back into the spotlight, though I’m sure the people of Wexford would say it’s always been in the spotlight.

Going much further back, Wexford was where the Normans landed to begin their invasion at the behest of Diarmaid Mac Murchada, who wanted help in retaking his kingship of Leinster. Diarmaid has a bad reputation in Irish history because of this, even though he was in reality just operating as any deposed king or lord of the medieval era would. It would have been standard practice to go into exile and seek aid from adventurers, landless knights, or anybody else willing to fight for the promise of riches and/or land. It just so happened that the Norman invasion of Leinster became the first part of the English conquest of Ireland under Henry II, though Diarmaid would not have contemplated such a thing happening.

In more recent centuries, Wexford was a major fighting ground during the 1798 rebellion, and many pikemen died battling British forces despite some initial successes. They were not all noble freedom fighters though; there were massacres by Catholics of Protestants, something which is often overlooked in the commemorations of the rebellion overall. The worst was at Scullabogue, where 150 Protestants, including woman and children, were slaughtered in a barn. It was the same day that the rebels had been crushed at New Ross, though I can’t remember correctly if historians have interpreted Scullabogue as a reaction to that defeat or if it just happened on the same day. Many rebels had died at New Ross and more would die after the town was captured.

One of the main battles was fought at Vinegar Hill. One of my college lecturers, Tom Dunne, grew up nearby and wrote a fascinating book about history and memory, using the 200th anniversary of the rebellion as a starting point. The book is as much a memoir as a historical textbook, dealing in parts with his own life and then historical debate about the rebellion (one of his ancestors died at New Ross), and particularly criticisms of historians who have tended to gloss over the less palatable aspects of the rebellion. You can read one of the earliest narratives of the overall rebellion here. A list of memorials is here.

Where else deserves a heritage trail? And should it mark the good as well as the ill?

Children are coming – they can forge their own path

The TV series Game of Thrones, and the book world of A Song of Ice and Fire generally, place great importance on heraldry and family. House Stark’s motto (or simply “their words”) is “Winter is coming”, House Lannister’s is “Hear me roar”, House Greyjoy’s is “We do not sow”. They serve to distinguish families from one another and often are a concise statement of what the family’s concerns are: the Starks urge one to be prepared, the Greyjoys show their contempt for farmers and the like, for instance.

George RR Martin is fascinated by heraldry, perhaps too much so. It works for his series, though, because it builds a complex and realistic world. He’s drawing on medieval Europe here, which had a very complex set of rules governing what could or couldn’t be on a family crest, although the book series doesn’t follow such rules. All families are concerned with heraldry, though, and individuals often have their own crests (or sigils, as they are called; and the ones shown in the TV series do not necessarily match those described in the books). Others might have a crest assigned to them by a more highborn lord, which is probably quite realistic too. There’s a full series on Westerosi families here, but as it’s based on the books be warned that many a spoiler lurks within.

The impending arrival of my younglings has had me dwelling a lot on family. It’s not actually a new interest/fascination. I’ve always taken family seriously, and certainly after it dawned on me some years ago that if I had no sons my particular family line could be kaput – I have no brothers and my sister has no children yet. That worried me in my own head for a while, worried me in a vague sort of way at least. I don’t know why. Families come along in their own time and I certainly don’t feel particularly old.

When I was a teenager I became fascinated by family history. I know bits and pieces of my own heritage – one grandfather was an architect, the other built cars and later ran a dock, for instance. Game of Thrones and its obsession with family seems to have reawakened that interest.

Generally speaking, my family seems to be descended from Mathghamhain, either the brother or nephew of Brian Boróimhe (I’ve read both at various times but haven’t made any serious genealogical study). For a youngster like myself, having some sort of tangential connection to a great historical figure such as a high king was, without a shadow of a doubt, cool. Any touristy genealogy stuff seems certain of it, but putting on my medievalist’s hat I tend to look somewhat cynically on such claims now, given that for centuries families across the world have claimed descent from legendary or mythical figures. Still, somewhere along the way was somebody called Mathghamhain (it means “bear”) and I am his descendant. As you’ve probably guessed by now, I like connections to the past, and having some of my own fascinates me; perhaps when I am older or have more time I will conduct a more in-depth study of my own family line.

The family crest also intrigued me, and I have no idea how it came about. Strictly speaking, I can’t use it, as I am not the head or heir apparent of the main line. I believe that is some guy in Orleans, presumably descended from one of the many Irish who left the country after the Battle of Kinsale and subsequent Flight of the Earls. The O’Mahony Society has its own crest. I’ve also come across two variations of the family motto, which wouldn’t be uncommon in history as different branches might adopt different stances or crests/mottoes depending on their individual circumstances. The one I came across first translates from Irish as “the burning torch to victory”, though this list of Irish mottoes only lists the other variation, which translates from Latin something like “thus we guard our sacred things”. My Latin is very rusty, though.

The family crest also intrigued me, and I have no idea how it came about. Strictly speaking, I can’t use it, as I am not the head or heir apparent of the main line. I believe that is some guy in Orleans, presumably descended from one of the many Irish who left the country after the Battle of Kinsale and subsequent Flight of the Earls. The O’Mahony Society has its own crest. I’ve also come across two variations of the family motto, which wouldn’t be uncommon in history as different branches might adopt different stances or crests/mottoes depending on their individual circumstances. The one I came across first translates from Irish as “the burning torch to victory”, though this list of Irish mottoes only lists the other variation, which translates from Latin something like “thus we guard our sacred things”. My Latin is very rusty, though.

Irish heraldry is somewhat complicated by the country’s history, with some coats of arms awarded after conquest by the English and others possibly dating to before that. The system of surrender and regrant, where Irish kings and lords swore fealty to the English crown and were given back their lands under new titles, such as earl, is probably a factor in this but I cannot say for certain. It’s not an exaggeration to say that almost all Irish people are descended from a king, as there were more than 100 across the island at one stage. Plus every Irish family had different septs (branches that held their own lands) so that adds an extra layer of complexity. Some will have Norman heritage (or Cambro-Norman), some will have Scottish, and various other backgrounds too. It’s all relevant or, perhaps more accurately, it’s all as relevant as you want it to be.

Some weeks ago I found myself wondering idly what I would do if I were in the position to create my own family crest and motto (as the Game of Thrones cast do in the video above). It’s possible, through the office of the chief herald, though I understand it costs a small fortune and I can’t see any that have been granted in the past few years so that could be defunct. It’s probably a bit pretentious, though it’s not like I’m trying to forge a dynasty or anything. I suppose it’s the idea of being able to forge one’s own destiny/heritage which caught my attention. What would I want to depict, and what would I want to say? Here’s what I’ve come up with on the right, based variously on the facts that I like cats, have “bear” as a surname, and work in newspapers. It just got me thinking about whether or not the words and sigils passed down through history are still relevant to me directly. Do I want my children to recognise their past and honour it in some vague way, or would I prefer them to start afresh?

Some weeks ago I found myself wondering idly what I would do if I were in the position to create my own family crest and motto (as the Game of Thrones cast do in the video above). It’s possible, through the office of the chief herald, though I understand it costs a small fortune and I can’t see any that have been granted in the past few years so that could be defunct. It’s probably a bit pretentious, though it’s not like I’m trying to forge a dynasty or anything. I suppose it’s the idea of being able to forge one’s own destiny/heritage which caught my attention. What would I want to depict, and what would I want to say? Here’s what I’ve come up with on the right, based variously on the facts that I like cats, have “bear” as a surname, and work in newspapers. It just got me thinking about whether or not the words and sigils passed down through history are still relevant to me directly. Do I want my children to recognise their past and honour it in some vague way, or would I prefer them to start afresh?

The truth is somewhere in between. The overall crest has a lot of historical relevance and is part of their (and mine) heritage. My wife is an O’Leary and her family is of similarly ancient lineage, so our little ones will have that heritage too. I look forward to seeing what they come up with.

Ancient treasure or vintage car spring?

Would you confuse this piece of gold with the spring from a vintage car? Well, one accidental treasure finder did (pic from The History Blog).

The torc, which has now gone on display in the Ulster Museum, Belfast, was found in a bog near Corrard, Co Fermanagh, which as far as I can tell is between Maguiresbridge and the Belle Isle Hotel. Google Maps is fairly blank on the region.

Anyway, Ronnie Johnston dug it up there, cleaned it off, and kept it in a cupboard for two years until he saw a picture of a torc in a magazine and thought it looked like the piece of twisted metal he had stashed away. His find is about 3,000 years old.

A coroner’s court agree it was treasure, and it was subsequently bought by Northern Ireland’s department of culture. The style links it to other finds in Ireland, the UK, and France, so it may suggest a cultural or trade link with those areas, or even the possibility that the owner came from there. We’ll never know, much as we’ll never know how it ended up in a bog (an offering, I suppose).

According to the Press Association:

Many mysteries still surround this gold torc. In its present condition the torc could not be worn as it has been deliberately coiled, appearing rather like a large spring. But the torc was originally designed to form a large circular hoop with two solid connections at either end. These are believed to have acted as interlocking clasps to allow the torc to be fastened and unfastened.

For me the main mystery is how somebody would confuse something that is clearly gold and not at all rusted with a piece of metal from a car. Or am I being cruel?

In the habit of praying

The Baltimore Sun has an interesting series at the moment on “Hidden Maryland”, various cultural aspects that would normally be overlooked. It has a piece up at the moment on the Carmeltie religious order, which I think is a nice way of showing how certain institutions can stay close to their historical roots while at the same time finding ways to make themselves more relevant to the current day:

For 185 years, the nuns practiced strict seclusion. They wore habits and veils, stayed behind grates when interacting with the public and rarely left the grounds.

Then came the Second Vatican Council, or Vatican II, which sought to modernize Roman Catholicism.

Baltimore Carmel, like many others, adapted. To some, it was a relief.

“I was fine with the old ways at the time, but the habits were heavy and hot, we looked like penguins, and I still have bald spots from the veils,” says a chuckling Sister Barbara Jean LaRochester, 80, who joined in the 1950s. “I’m glad we left those days behind.”

I have a fondness for monasteries, though it doesn’t have anything to do with Bede. It’s something to do with the quietness and pace of life, which may be a quietness and slow pace that exists only in my head for all I know.

$250,000 in Gold Coins Discovered Off Florida Coast

Oh if only I could make a find like that in my back garden…

Ice Age art

A few months ago I was lucky enough to get to the British Museum exhibition on Ice Age art, called “The Arrival of the Modern Mind”. I have to say it was on a par with the larger, much grander and more popular Pompeii exhibit, which was also brilliant.

Unfortunately I don’t have any photos of my own; snaps were banned, which is understandable given the delicate nature of the items and commercial rights of various museums. The main theme of the art exhibition was that the styles and techniques of the earliest human artists were strikingly similar to what we would consider modern art. Picasso, known for his abstract depictions of women, was heavily inspired by a neolithic carving of a woman; he kept two casts of it in his studio. The exhibit curators had also sourced recent paintings that had similar brush stroke and compositional techniques to our early ancestors.

Seeing such tiny and delicate things in front of me through the glass, I was struck not only by their beauty but their fragility and the amount of effort it took to produce them. Some of these pieces were 40,000 years old. One bone carving of a human with a lion’s head was estimated to have taken over 400 hours to create.

When you consider that these people were hunter-gatherers, and so always on the borderline in terms of starvation, that they would commit so much of themselves to producing such art shows that the human creative genius must have always needed an outlet. Whether it was for ritual or decorative purposes, these people had an idea and took whatever time was necessary for that idea to come to fruition. We tend to think of our ancestors as primitive, but they don’t seem to have been too far behind us in many respects.

I’ve noted previously how much people of the here and now and antiquity enjoyed having little objets d’arts scattered about, and our ancient ancestors were no different, with tiny little lion-men as well as water birds.

When you think about how little has made it to us from so long ago, it makes you wonder what will be left of us in 40,000 years apart from plastic bottles.