The rebuilt abbey of Iona

This year marks the 1,450th anniversary of St Columba’s arrival on the island of Iona, off the coast of Scotland. If you’ve read your Bede well (as I know you have) then you’ll remember him as one of the paramount evangelists to northern Britain.

Pictish kingdoms; the Irish Dál Riata is the large area to the southwest

Columba (d. AD597) is of vital importance for early medieval insular studies, because the monastery he founded at Iona became one of the most influential in Ireland or Britain. Its monks went on to evangelise not only the Picts but the English, founding the likes of Lindisfarne, which in turn became one of the most important religious sites in Northumbria. Bede praises the Irish for having brought Christianity to the English when the Britons, the Christian descendants of the Romano-Celtic population, had refused and remained apart.

Columba was one of the many Irish who ended up in “exile for Christ” (peregrinatio), though in his case the story is that he had to leave Ireland after many people died in a battle over a manuscript of hymns (they took their hymn books seriously in those days). He fled Donegal for Iona, which then was part of the Irish kingdom of Dál Riata, which incorporated the northeast of Ireland and southwest of modern Scotland.

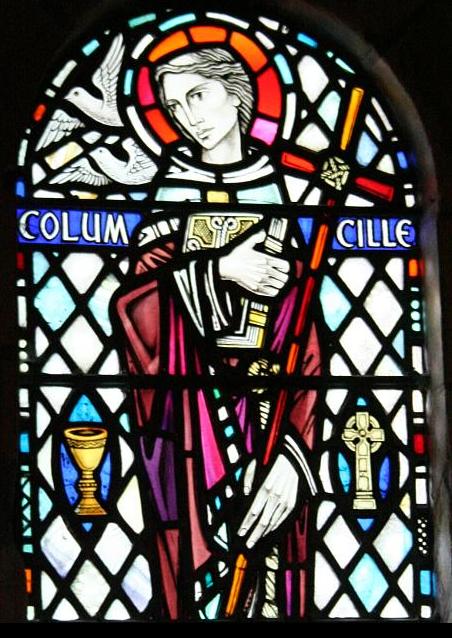

Columba commemorated in stained glass at the abbey

What tends to be overlooked is that he is one of the three patron saints of Ireland. Everybody knows Patrick, and everybody has heard of Brigid, but Columba (or Colmcille as he was known in Irish) is less well known across most of our island. His missionary endeavours and monastic founding spree make him a saint par excellence, particularly because Christianity was still bedding in somewhat amongst the Irish and Picts at his time and hadn’t taken off at all among the English. His groundwork, then, contributed to the shaping of the islands’ history.

Fun fact: The first recording of a monstrous creature near Loch Ness is in Adomnán’s Life of Columba. The creature had killed a Pict and was about to eat one of Columba’s monks, but he banished it to the waters with the power of prayer.

I quite like the Life of Columba as a text. It has a lot of the standard imagery of medieval hagiography, a genre which is rich in miracle stories and other events without intending to be strictly historical. They contain basic biographical details, but are designed to commemorate the memory of a saint and to spread his or her cult, as well as holding the saint up as an example of how to live a good Christian life.

The Life of Columba is particularly important because it was written at a very early stage of Christianity in Ireland, and yet it is completely engaged with the genre, showing that the author, Adomnán, abbot of Iona (d. AD704), had read widely and knew exactly how to shape the tale of his predecessor in order to promote his memory. He shows that Columba was saint on a par with any saint from the Holy Land or continental Europe.

For example, he is granted prophetic visions as well as the power to work miracles; indeed, one of the final miraculous events in the Life is Columba foreseeing his own death. And following his death, Adomnán writes:

After his soul had left the tabernacle of the body, his face still continued ruddy, and brightened in a wonderful way by his vision of the angels, and that to such a degree that he had the appearance, not so much of one dead, as of one alive and sleeping

It is a political as well as religious text, because Iona was under particular pressure at that stage because it was out of step with Rome and Britain on the calculation of Easter. This might not seem like a big thing to us, but it was profound then, because it meant that the church at Iona was effectively outside Christian orthodoxy. Part of Adomnán’s motivation was to show that the founder of Iona was favoured by God, which in turn would have strengthened Iona’s case for holding to the old Easter calculation.

Quite what Columba, a man who had converted kings and been a prolific writer, would have thought is unknown. Still, his legacy is uncontestable, and President Michael D Higgins has urged contemporary Irish emigrants to consider his example:

Modern migrants do not generally make decisions in such dramatic circumstances as Colmcille’s but, whether they see themselves as exiles or not, at some point many will ask themselves what they have to share and to teach to their new neighbours; how they may influence the society in which they make their new home; and what they may absorb there, changing themselves in the process.

It’s sound advice. I think Columba would have agreed.

Great post, Mr. O’Mahony, thanks – and a beautiful opening pic of Iona! I’ve sadly never come near the place myself, and all the photos I’ve seen until now have been quite grey and dreary.

I’m curious – when you mention Iona keeping “the old Easter calculation”, do you mean that the British(/Irish?) calculation was older than the one that was eventually settled upon? I’d think the Roman method of calculation would be older, but perhaps the Roman calculation itself had undergone some changes?

The quote from President Higgins is interesting as well – unusual, from my US perspective, to see a president discussing EMigration!

Hi Medieval Dad,

I didn’t phrase it properly. I meant “old” in an British/Irish context, because they would have considered the Roman reform “new” in that they hadn’t used it before. The problem for years was that the Council of Nicaea had said that all churches should follow one Easter, but it did not enforce a single method for calculating it. There were a few different methods in use in different places at the same time but eventually one won out.

However, it wasn’t until 664 that the northern English church came into line, and a few decades after that before the last Ionan-influenced regions and Iona itself converted. Bede, who is one of our best sources for this, presents it as a reward for the Irish who had spent so long preaching to their pagan English neighbours.

Ah, I see.

Bede had to walk a fine line there, I guess – needing/wanting to hold up the tradition of Iona as a paragon of Christianity in comparison to the British churches, and so probably not wanting to portray Iona’s submission to the Roman calculation as an in-your-face slam dunk. It’s been a while since I’ve read on this issue; I’d forgotten his presentation of it.